SOUTHERN GAZA - WATER

Gaza has historically relied on its local freshwater sources for drinking, sanitation, and agriculture. This includes wellwater, springs, rainfall, and the Wadi. Yet, decades of overextraction, contamination, and foreign control and destruction have left the region’s water systems depleted and fragile. Today, the systemic targeting of infrastructure combined with the displacement of Gazans and restriction of aide has created a crisis.

Water Crisis Media Coverage

Khan Yunis Wastewater Treatment Plant

The upper intermediate map (magnified left) integrates Forensic Architecture’s well functionality data (right) with a topographic representation of the Al-Mawasi Humanitarian Zone in the Rafah and Khan Yunis regions.

Destruction of water infrastructure is vast. The data on destroyed facilities may not even capture the reality, as demonstrated by the below before and after shots. While this facility is technically not fully destroyed (the large water tank appears to still be standing) the most recent satellite imagery shows the smaller buildings in the facility were destroyed in the targeting and therefore the functionality of the infrastructure may in fact be zero. The destroyed area may also be fully inaccessible and render water capacity completely inaccessible.

The below vertical, layered cartographic model visualizes wellwater access and control in southern Gaza. Allegedly functional wells appear in blue, while destroyed wells are marked in red. Positioned between a topographic map of southern Gaza and the underground Mediterranean Coastal Aquifer, two intermediate maps highlight contrasting experiences: one illustrating limited access for Gazans in the Al-Mawasi Humanitarian Zone, and the other demonstrating how Israeli control overlaps with regions of critical water access, emphasizing stark disparities in availability and resource control and more accurately reflecting the lived experience in Gaza.

The water from the Coastal Aquifer is brackish and contaminated due to seawater intrusion, overextraction, and sewage and chemical infiltration (see above) and therefore Gazans rely on small-scale desalination units (when possible) and unregulated private water tankers.

Both desalination units in southern Gaza as well as the majority of accessible wells have been damaged, destroyed, or are currently under Israeli control.

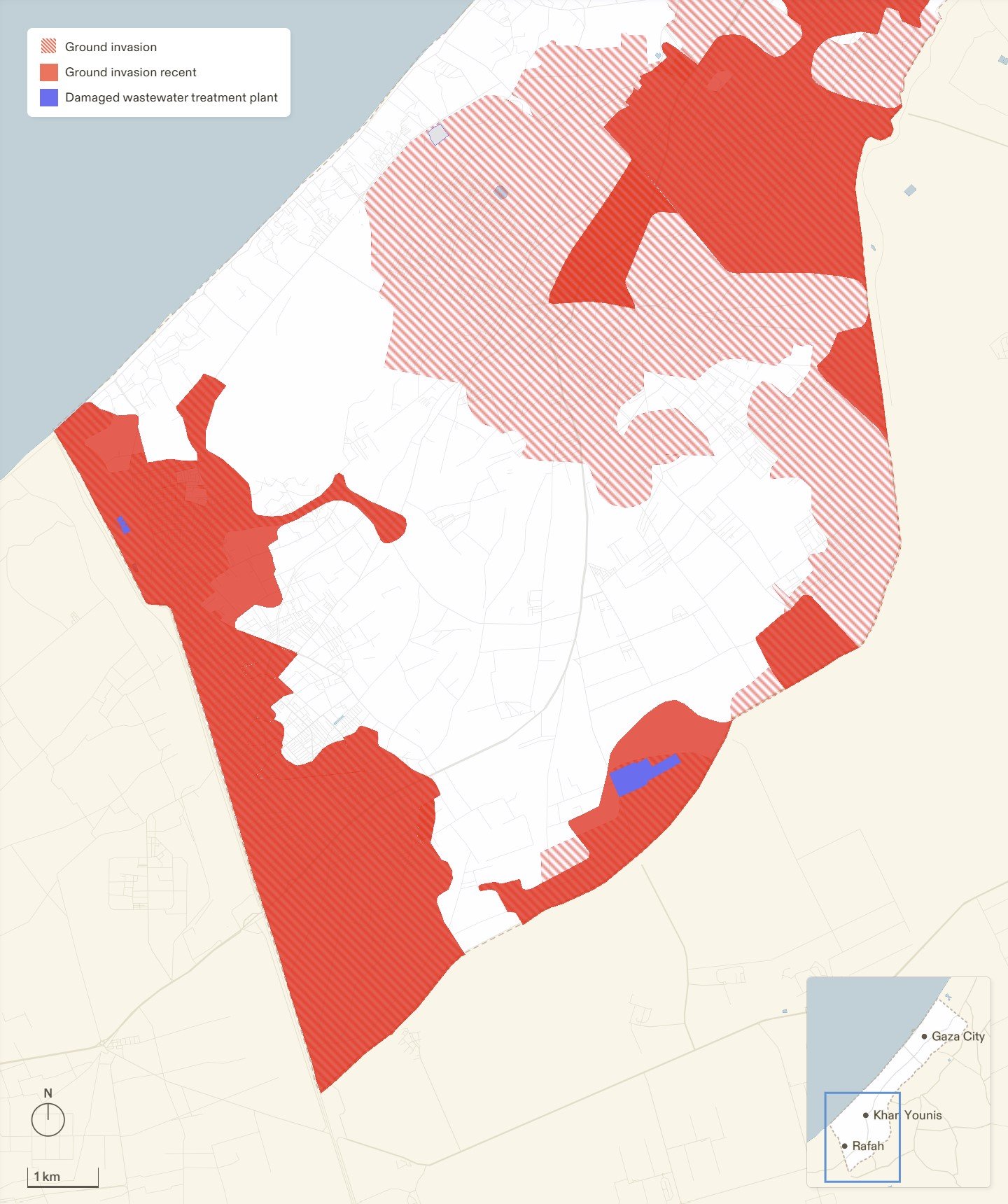

Although the map (right) shows intact water wells in Rafah in blue, the lived reality, demonstrated with the below two maps and further analysis, reveals that Gazans have been evacuated into an area with minimal functional well accessibility while the Israeli army controls the southern most area in Rafah with the majority of functional water access.

Video (above) and graph (below) show Gaza’s water crisis is not new

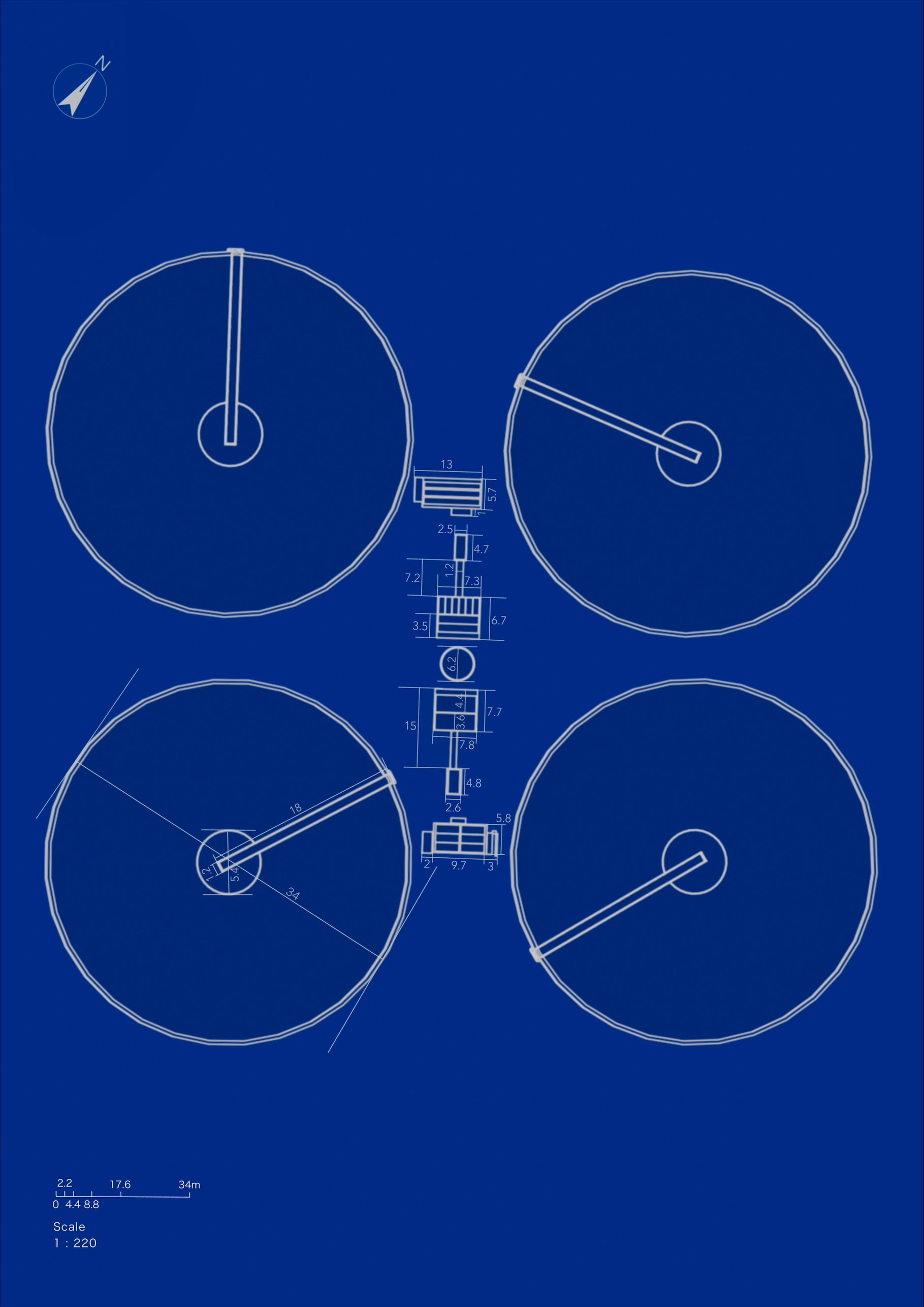

This architectural perspective (right) of the water clarification tanks at the Khan Yunis Wastewater Treatment Plant examines themes of control, cultural heritage, and reclamation within the context of Gaza’s ongoing water crisis. Inspired by and pulling from Jumana Emil Abboud's The Pomegranate and the Sleeping Ghoul, the perspective highlights water infrastructure as both a tool of disempowerment and a potential site of reclamation, underscoring water's deep spiritual and cultural significance in Palestinian heritage while contrasting this with its current weaponization, foreign control, and inaccessibility.

The clarification tanks’ function of filtering and separating particles mirrors the displacement and occupation faced by Gazans—processes imposed externally and removing agency for those it affects. The tanks also reflect the lived reality with respect to water in Gaza, where containers and storage of all types are daily necessities. By highlighting the distance between the industrial scale of wastewater treatment with the critical daily practices of water collection familiar to Gazans, the work exposes the disconnect between large-scale development projects and the immediate needs of those they claim to serve.

Visually, the perspective adopts a Palestinian design ethos, incorporating colors and textures that evoke Palestinian culture and art and pulling from the mystical importance of water in much of Abboud’s work. This aesthetic departure from typical foreign development reports (included above) critiques the portrayal of such projects as neutral or benevolent, instead highlighting the disconnect from local agency when these projects are rooted in foreign development and control and contrasting that with a vision that reclaims infrastructure and agency for Gazans.

Ultimately, this perspective situates the clarification tanks within both Gaza’s broader water crisis and the Palestinian struggle for sovereignty, critiquing the cycle of destruction and reconstruction that renders essential infrastructure transient and unsustainable. By reframing the tanks as symbols of both loss and the potential for reclamation, the work envisions a future rooted in cultural sovereignty and resilience.

The lower intermediate map (magnified left) overlays Forensic Architecture’s well functionality data (right) onto a topographic map of the region invaded by the Israeli army. Notably, the southern Rafah area, where most of the undamaged wells are located, falls under Israeli control, likely highlighting the strategic decisions behind the Israeli army’s area of invasion and area of targeted bombardment.

The pomegranate and the sleeping ghoul, Jumana Emil Abboud

Plan of Clarification Tanks at KYWTP

The destruction of the Khan Yunis Wastewater Treatment Plant comes less than two years after its completion. The investment and destruction cycle of this largescale facility illustrates the tenuous structure of foreign development in an occupied territory and should provoke action that refocuses efforts on sovereignty and longterm resilliance.

A clarification tank, also called a clarifier, is a large open tank used in water treatment processes to remove suspended solids from a liquid by allowing heavier particles to settle to the bottom through gravity, essentially separating the solid particles from the clean water that can then be collected at the top.

Khan Yunis, prior to the mass evacuation following Oct 7th, was inhabited by more than 340,000 residents. It had an absolute absence of a functional wastewater treatment plant. The raw sewage was still being disposed off in the environment without treatment through cesspits and ad-hoc lagoons, which was posing serious risks to the residents’ public health as well as contaminating the ground water aquifer.

The construction of Khan Younis Wastewater Treatment Plant was prioritized by the Palestinian Water Authority (PWA) as a strategic environmental and developmental project that not only needed to respond to the vital hygienic and environmental needs of Khan Yunis residents, but to also fulfil the PWA’s objectives in achieving water security in the Gaza Strip.

The project was funded by the United Nations Development Programme, the government of Japan, the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development, and the Islamic Development Bank.

KYWTP Study

The Khan Yunis Wastewater Treatment Plant serves as a critical focus within the broader context of Gaza’s water crisis, illustrating the use of water infrastructure as a tool of war and the systemic targeting of essential resources under occupation. This site encapsulates the disconnection between large-scale foreign development projects and the immediate, lived needs of Gazans, highlighting the vulnerability of infrastructure to destruction and its role in enforcing dependence. By studying this plant, the project interrogates the intersections of survival, resilience, and political control while envisioning future city design rooted in Palestinian agency, cultural heritage, and the reclamation of water as a source of autonomy and collective liberation.

95% - 99% of Palestinian water supply in the Gaza Strip comes from groundwater. The other major natural source is the Wadi, which provides floodwater for agriculture.

According to the Palestinian Water Authority, 97% of Gaza’s Coastal aquifer is not suitable for drinking purposes and needs heavy filtration.

The major water quality problems are high salinity and high nitrate and chloride concentrations in the aquifer. The high salinity levels are the result of over-extraction from the shared aquifer (largely to supply Israeli water needs), which causes draw-down of the groundwater (resulting in seawater intrusion).

The quality of the groundwater in this aquifer is further compromised by the discharge of untreated domestic wastewater into the Mediterranean Sea on the coast of Gaza due to a lack of wastewater treatment infrastructure. This wastewater is absorbed into the aquifer at high rates due to overextraction of the aquifer and thus polluted seawater intrusion.

On the whole, media coverage has painted the water crisis as an unfortunate byproduct of the war that is leading to illness and death. Deeper analysis of this crisis, found in longform reports and forensic mapping, highlights the systemic targeting of water sources by the Israeli military — an active practice for many decades now. Cartographic analysis also demonstrates that the majority of intact water systems are under Israeli control in Gaza.

Geographical & Aquifer Analysis

Rainfall in the Gaza strip is light, around 356mm/y

Gaza’s Current Water Crisis

Contrasting the above perspective, the rendered model here of the Khan Yunis clarification tanks emerges as a stark, ghostly vision in black and white, embodying the emptiness of a site stripped of life and purpose. The tanks, skeletal and hollow, stand as relics of foreign development—a failed intervention now inoperable and abandoned. Shadows stretch across the barren tanks and the absence of water and movement accentuates the emptiness and stillness of the space.

The tanks here are not symbols of life, productivity, or technology but as the remnants of a cycle of investment and devastation, disconnected from the lived needs of Gazans. The lack of detail in the surroundings heightens the eerie quality and disconnects this project from space and time. In this depiction, the tanks serve as haunting reminders of the fragility and failure of imposed foreign solutions in a context where autonomy is systematically undermined.

Wells & Treatment Plants

All seven wastewater treatment plants in Gaza have been damaged and are either partially or fully inoperational (below). The al-Mawasi Humanitarian Zone, where more than 1 million are currently sheltering, is seeing an exponential increase in sewage output into the Mediterranean Sea that will undoubtable be absorbed into the coastal aquifer.

Further exacerbating the current and future state of the Aquifer is Israel’s actions to flood Gaza’s tunnels. Although they claim this is to counter Hamas military movements, it has the direct effect of targeting Gaza’s current and water supply.

Since October 7, 2023, the state of Palestine has faced unprecedented Israeli aggression in the Gaza Strip, essentially levelling water infrastructure and supply. Historically reliant on approximately 300 groundwater wells, Gaza's water production has been drastically reduced to just 10% of pre-conflict levels . The situation is compounded by the fact that water connections from Mekorot, Israel's national water company, were halted amidst escalating tensions. Desalination plants, crucial for supplementing and purifying Gaza's water supply, have been damaged, destroyed or are crippled due to restrictions on importing fuel and chemicals essential for their operation. Access to water vendors and bottled water has become increasingly scarce due to insecurity and import limitations. This has heightened the risk of waterborne diseases and compounded health challenges for Gaza's population as they struggle with deteriorating access to clean water.

Gaza pulls its underground water from the Mediterranean Coastal Aquifer. The major source of renewable groundwater in the aquifer is rainfall. Some recharge is available from the major surface flow of the Wadi. However, because of the extensive extraction from Wadi by Israel, this recharge is limited to, at best, 2 MCM during the ten days the Wadi actually flows in a normal year.

Khan Yunis Wastewater Treatment Plant Areal View

Indiscriminate destruction (right) consequently destroys water infrastructure.

Compounding Gazan’s access to functional wells is the fact that both major wastewater treatment plants in South Gaza have been damaged or fully destroyed (right), and both are currently under Israeli control (below)