Virtual Tour

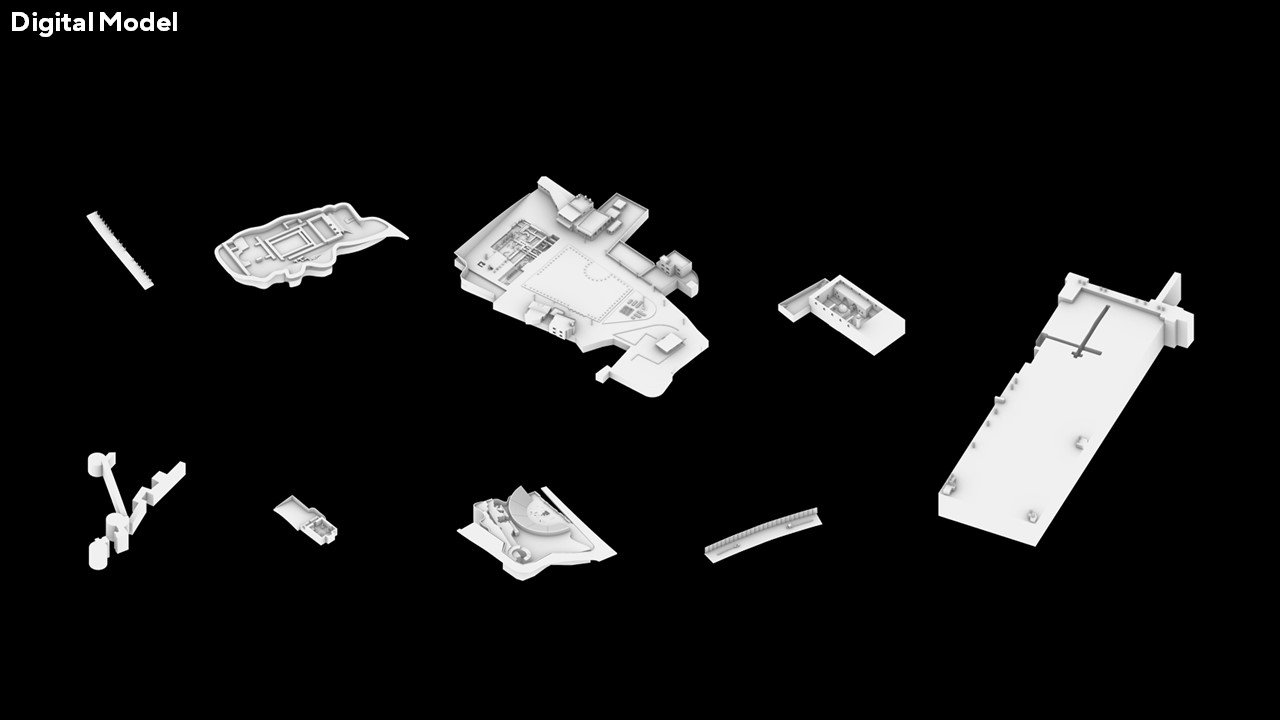

Tourism in Sebastia is a reflection of the political character of the West Bank. The project aims to understand the irrationality of Sebastia's politics and tourism through the relationship between site and movement, from the perspective of the visitor, and to critically consider whether the existence of a national park is justified. The project uses modelling and rendering to create a fictionalised version of Sebastia without the existence of the National Park, and the story line in the film explains the unfair outcomes of the Oslo Accords and the National Park Law for Palestine by arranging a series of unusual tourist sites. The project aims to use spatial analysis and movement to make politics understandable to the visitor.

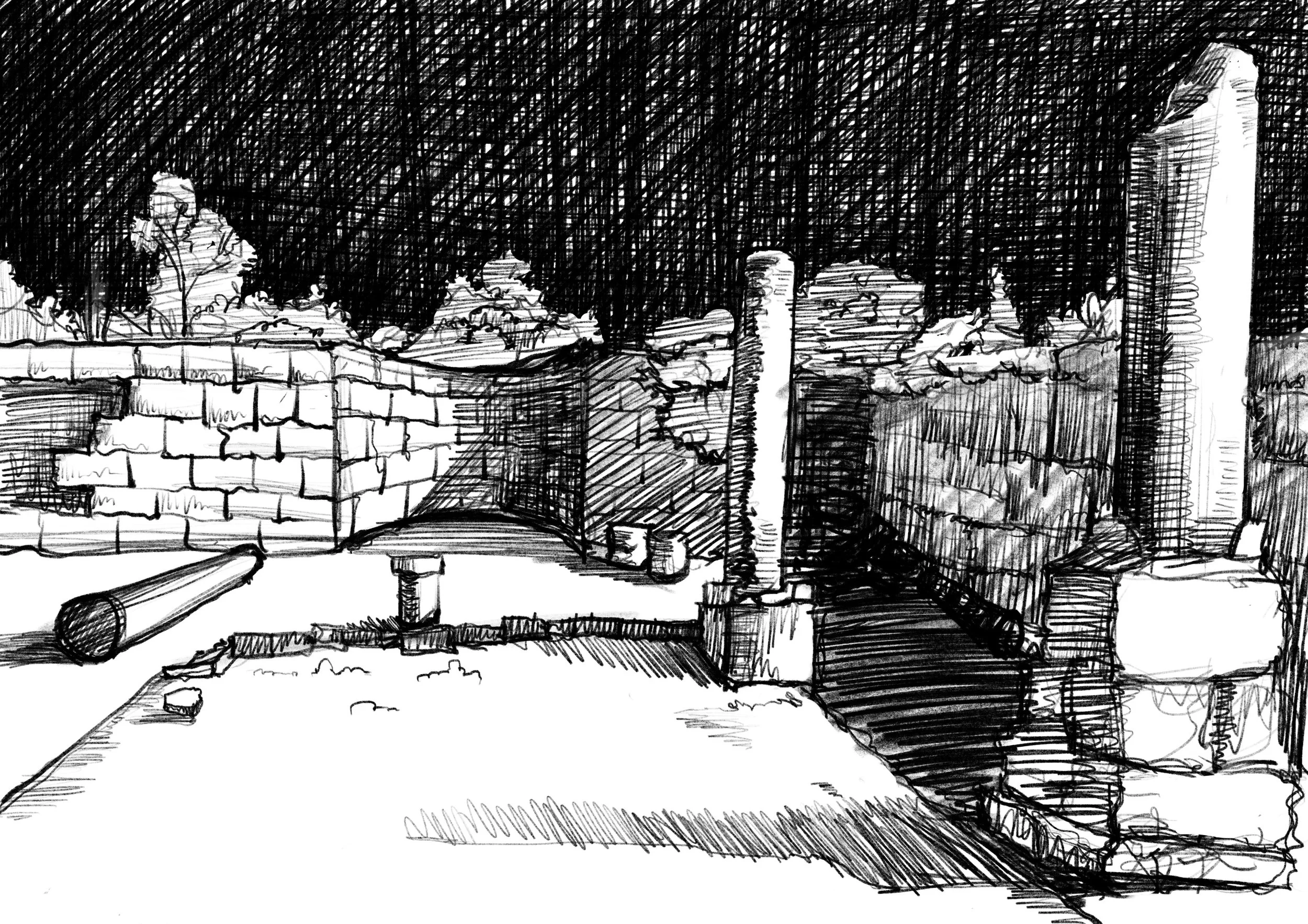

Draft

Footages

Research

Highway 60

Shavei Shomron

Checkpoint

Gate

Column Street

West Gate

Guesthouse

Forum

Theatre

Acropolic

Church

Mosque

Harvest

Destroy

Virtual Tour for Diasporas

Women and children from a Palestinian village near Haifa walk through no man’s land to Tulkarm in the West Bank during a truce between the Israeli and Arab armies, Palestine, 26 June 1948.

After the wars of 1948 and 1967, Israeli Zionism occupied large areas of Palestine. The first mass migration in Palestine took place and many Palestinians who had been living in the occupied areas were forcibly displaced and became refugees from the war. They were forced to leave their homes and go into exile, and had to obtain permission from Israel to return home. Today, Palestinian diasporas living in different countries have established Palestinian communities, who continue to carry on their Palestinian cultural life and sense of nationhood abroad, and continue to work in solidarity with Palestine. The project examines the current situation of Palestinian diasporas living abroad and designs a virtual reality project for the expatriates. Using Sebastia as an example, the project allows the diaspora to immersively explore the story of what is happening in the land of Palestine in virtual games, using virtual technology to bring diasporas back to Palestine. The project is a way of breaking down geographical and policy boundaries in a way that is anti-apartheid.

Process of Game

The project focuses on an immersive tour of Sebastia for the Palestinian diasporas through Virtual Game, a medium that connects the diaspora to Palestine, breaking down geographical and political borders and bringing the Palestinian diaspora back to their homeland. The initial proposal for the project was based on research. Tourism was the entry point for my research on Sebastia, which encompasses various aspects from the past to the present: history, culture, ethnicity, architecture, landscape, politics, etc. It is also the main way in which a city is promoted to the outside world. When a stranger wants to get to know a city, tourism is the best way to do so, because he can experience the most characteristic aspects of the city in the shortest possible time. In my research on Sebastia, I have organised the texts, pictures and videos I have collected into a framework, and found that they take the form of interviews, travel journals, propaganda films and factual accounts, most of which are statements about Sebastia’s culture and the current political situation. While the residents of Sebastia are trying to promote their town, they are also using the media to expose the truth about the destruction caused by Israeli settlers in Sebastia.

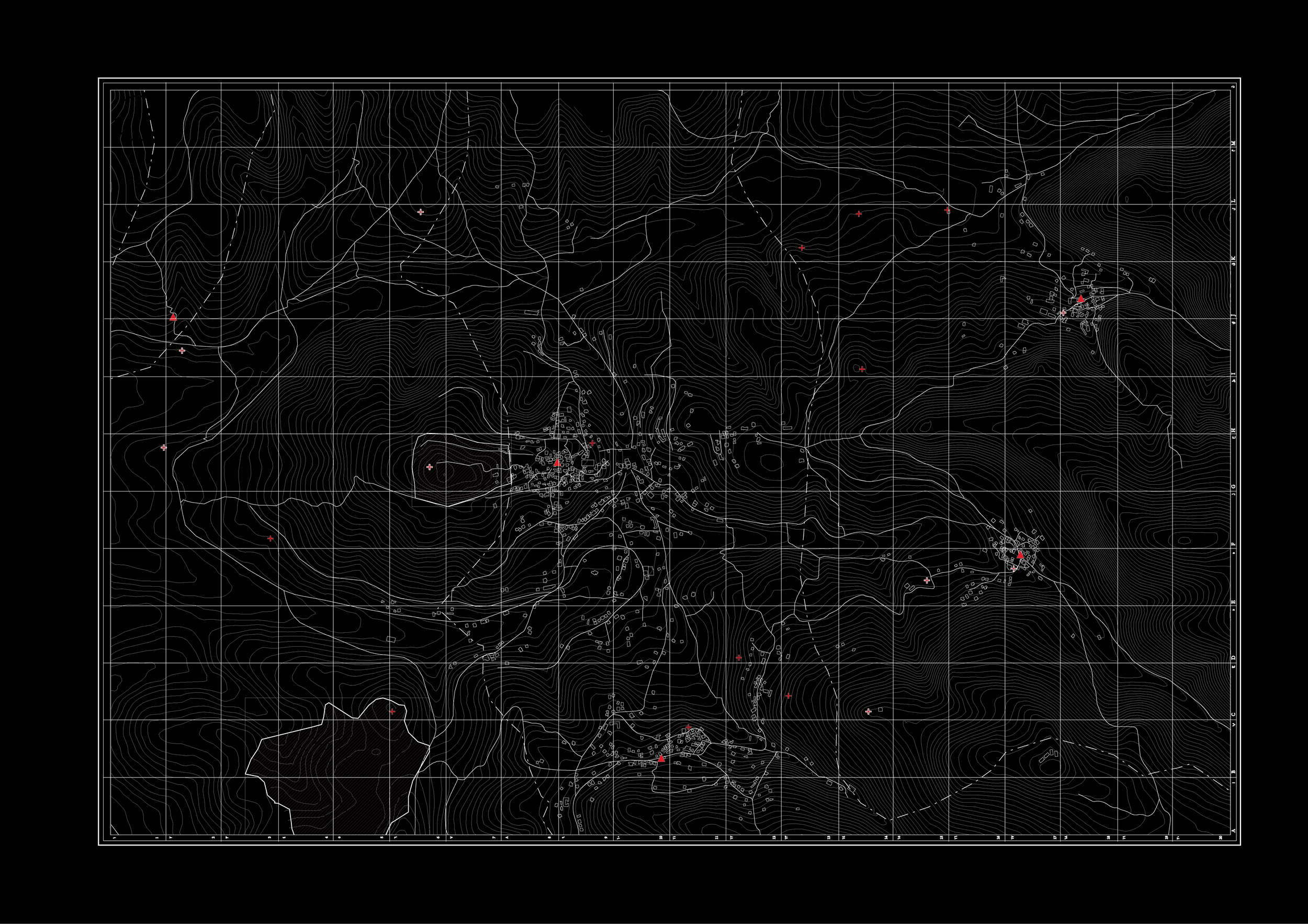

Anti-apartheid Map

Maps reflect and perpetuate power relations, often expressing the interests of dominant groups, and the intricacies of nineteenth-century colonialism and imperialism were reflected in cartography, where cartographers drew lines on paper as boundaries separating human resources. Another example is the Mercator projection commonly used for world maps, which is an inaccurate representation because when cartographers ‘flatten’ the earth, they need to make certain choices: size, shape and distance will all be different from the real world. Maps are not just neutral tools, but strategic weapons for expressing power. Grassroots groups and individuals can also use mapping for a variety of purposes. Maps can be used to make counter-claims, to make marginalised and hidden histories visible, to develop practical plans for social change or to imagine utopian worlds1. Many NGOs and charities enable indigenous communities to map their territories in order to make land claims and protect resources from capital appropriation. It is worth noting that the maps do not need to be drawn on paper, nor do they have to be two-dimensional.

The map that the project finally expects to come up with is done by the Palestinian diaspora, who express their determination as a diaspora to want to return to Palestine, as a bottom-up mapping device. The virtual world itself is a map, it is not two-dimensional. The game engine maps all real facts and virtual non-realities, and the players become part of the map in the virtual world. Whatever route they have chosen to visit, once the game starts they can walk through the virtual Sebastia as they choose, without being restricted by so-called policies and walls of isolation. Everyone will have their own choice and therefore everyone will generate their own map in which they can also put forward their ideas, making the anti-apartheid cartography even more powerful.